Today I’m going to talk to you about the differences between men and women, also the subject of my first book. Or, more precisely, I’m going to talk about how the idea that men and women come from different planets shapes our worlds and influences women’s lives and careers.

But first, I would like to make a confession. Until about eleven years ago, I was a strong believer in the whole ‘Men are from Mars, women from Venus’-idea. At the time I was living with my soon to be ex-boyfriend. He wasn’t much of a talker. Instead he spent most of the days and evenings playing computer games, only getting away from his pc to ask me if I’d cooked dinner yet.

After a couple of weeks I decided I couldn’t take this much longer, and that something had to be done. And then I made a big mistake: instead of packing my bags and leaving him, I went to the bookstore. There I found several shelves of books, by, amongst others, Barbara and Allan Pease and John Gray, loosely based on evolutionary psychology, which explained the behaviour of my douche-bag boyfriend to me. Men aren’t build to communicate extensively, these books said, because in the stone age they would be out with other men, quietly hunting mammoths. Prehistoric women, on the other hand, spent their days sitting around the cave, taking care of the children and gossiping with their fellow cave women. Therefore modern women now want to talk to their men, but men would still rather stay quiet and hunt large animals. Or, in my ex-boyfriend’s case: shoot orcs on a computer screen.

Women, these books told me, also naturally find great pleasure in taking care of their men, being innately more nurturing. In prehistoric times they would prepare the meals, because their cave-husband would be too tired after aforementioned hunting.

So, in short: my boyfriend’s behaviour was perfectly normal. It was me that was off, not finding this great sense of fulfilment in being ignored all day and then cooking him a fancy dinner.

After I realised this, I tried to embrace my inner cave woman. I would stop complaining, and take care of all the chores, hoping it would somehow make me happier if I lived true to my innate femininity. I lasted about three weeks. Then I packed my bags and left him after all. A couple of months later I met a great guy, who loves to talk to me, hardly ever plays computer games and is a lovely cook to boot. We have been together for ten years this month.

=

Because, you see, these stories about how women are fundamentally different from men, because of some obscure prehistoric past, are, well, all crap. Not because they didn’t work out for me, but because these evolutionary psychology-writers take a 1950’s view of how gender should relate to each other and project it back hundreds of thousands of years. She the happy housewife, he the provider of the family. It’s like feminism’s second wave never happened.

The truth is that nobody really knows what happened when we were still homo erectus or early homo sapiens. Since behavioural patterns can’t be dug up by archeologists, there is no clear evidence that one gender exclusively took care of one task while the other was exclusively focused on the other—childbearing and nursing aside. There is also no evidence whatsoever that suggests that modern men and women have evolved to have different skills, desires or talents.

The reason I’m so sure about this, is science. If men and women were naturally inclined to living very different lives, they would be, well, very different. Yet this is not the case. In a large meta-analysis performed in 2005 by the psychologist Janet Shibley Hyde, she reviews over 250 effect sizes, taken from over 40 different studies on the topic of sex differences. All kinds of possible differences are included in the analysis: from the understanding of mathematical concepts to self-esteem, from helping behaviour to aggression when provoked, and from leadership style to cheating behaviour.

Comparing all these effect sizes, Hyde concludes that – and I quote – “males and females are similar on most, but not all, psychological variables. That is, men and women, as well as boys and girls, are more alike than they are different.”

“Most, but not all”? Yes, there were some firm differences between the sexes. Men, for instance, throw a ball at much greater speed and along a much greater distance than women. They also claim to masturbate more often. That was about it. Even on measurements of physical aggression, the difference between Mars and Venus remained small to moderate.

Last February Hyde’s conclusions were confirmed by a group of psychologists from the University of Rochester. They re-analysed data from 13 well executed studies on sex differences in personality traits. Using advanced statistics they tried to find some indication that men and women were indeed two totally different ‘subspecies’ in our population, with all men on one side, being all rational and tough and technical, and all women on the other, being all empathic and sweet and social, like the idea of Mars and Venus would suggest.

They found no such thing. Even on the personality treat ‘masculinity’, there was no clear sex difference to be found. Instead, the data indicated there is a scale which goes from male to female, and every single trait an individual has, can be placed somewhere on this scale. This means that a single individual can for instance be more feminine in some aspects of her personality, and more masculine on others. Everyone’s character is a unique mixture of both genders, uniting female and male in themselves. We are not yin or yang. We are all both.

This view matches perfectly with what we know about male and female brains. It is true that there are mountains and mountains of research zooming in on this neuro sex difference or that. And, as the Australian neuropsychologist Cordelia Fine says, that’s hardly surprising. Female brains are a bit smaller than male brains, so of course you would find some anatomical and functional differences. The real question is: do these sex differences on the brain lead to different behaviour or abilities? Obviously, given the previous two studies I discussed, the answer is ‘no’. At which point Fine poses a very probable hypothesis: that female brains look and function differently from males, just to make up for their smaller size. That all these neuro sex differences exist just so women can do exactly the same things as men, despite their somewhat tinier brain.

So, you see, we are not from different planets after all.

=

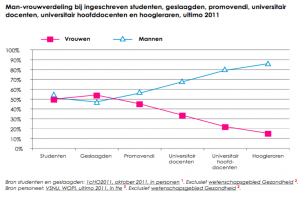

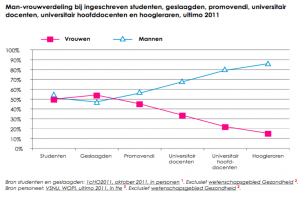

This raises a couple of important questions. For instance: if men aren’t from Mars and women aren’t from Venus, than why are most bèta scientists male? Why does the average women in the Netherlands earn a salary that’s 8 percent lower that a men with the same job, education and experience? And why is a majority of all university graduates female but only 14.8 percent of all professors?

The answer is: stereotypes. Because even though men and women aren’t really all that different, research shows that almost all of us, on some level, consciously or unconsciously, believe they are. And like a placebo can cure a person just by making him or her believe that it will, this idea of Mars and Venus is so powerful that it can create differences that were never really there. In this way, stereotypes hold great power over our lives, all too often making themselves come true.

This process starts even before we are born. From the moment expecting mothers find out the sex of their child, the ones that are pregnant with boys start reporting more kicking and turning about than the ones that are pregnant with girls. In fact male and female fetuses are equally active. What the mothers are feeling is the effect of the cultural stereotype that boys are wilder than girls, little soccer players compared to little ballerina’s. And what they believe becomes what they feel.

After birth the stereotyping continues. Parents who didn’t know the sex of their baby before birth are immediately informed it’s a boy or a girl, often even before they are told wether the baby looks healthy or not. Research shows that nurses call newborn boys pet names like ‘tough guy’ or ‘tiger’ while they call the girls ‘sweetie’ of ‘princess’. In the early months parents – unconsciously – talk more to their daughters than to their sons. They also discuss emotions in greater detail with their daughters, and if she cries, they will be quicker to pick her up and comfort her than they would a boy.

An ingenious experiment by Wilberta Donovan from the University of Wisconsin-Madison shows that mother are even less attuned to boys emotions than they are to girls. In 2006 she invited 69 mothers to her lab. All had given birth in the past six month, so they were in full baby mode. All these mothers were shone a series of pictures of a gender-neutrally dressed baby experiencing various emotions. Sometimes the baby was crying, sometimes smiling, sometimes something in between. The mothers were asked to tell what kind of emotion the baby showed.

Now to the part where it gets interesting. Before the mother sat down to look at the pictures, Donovan told half of them they were looking at a baby girl named Sara, and the other half that they were looking at a little boy named Henry. And that made all the difference. The mothers that thought they were looking at Sara were able to recognize much more different kinds of emotions than the mums who thought they were looking at Henry. Remember, they all looked at the same set of pictures. It was just the idea of looking at a boy that made them less sensitive to his emotions.

And that’s only what happens to baby boys and girls at home. The outside world is even more thoroughly gendered, with pink and sweet and passive princesses and being beautiful for girls, and blue and cars and sports and being aggressive and competitive for boys. I’ll show you some examples I’ve posted on my blog, where I collect photo’s of everyday sexism in stores, media and advertising.

(In the Disney store: Be a hero shirt for boys vs I need a hero for girls)

As a side note: these pink versus blue gendering of the world children live in has only gotten worse in the last couple of years, research by sociologist Elizabeth Sweet of the University of California in Davis shows. I interviewed her for an article on the sexualization of girls toys I’ve written this spring, and she told me that in 1975, very few toys were explicitly marketed according to gender, and nearly 70 percent showed no markings of gender whatsoever. In the 1970s, toy ads often defied gender stereotypes by showing girls building and playing airplane captain, and boys cooking in the kitchen.

But by 1995, the gendered advertising of toys had crept back to midcentury levels, and it’s even more extreme today. In fact, finding a toy that is not marketed either explicitly or subtly (for instance by, as Elizabeth Sweet calls it, ‘pinkwashing’) by gender has become incredibly difficult. It is, again, like the second wave of feminism never happened.

=

So, what are the consequences of all this stereotyping, specifically for girls and women? Even though it doesn’t change our innate traits or abilities, it changes how we act and the choices we make. For instance: even though there is hardly any evidence that women are more nurturing than men, when a heterosexual couple is expecting a child it is far more likely that the woman will stop working or cut down on her hours to take care of the baby than the man.

Of course, some evolutionary psychologists would say that such a choice again reflects the situation as it has been for hundreds and hundreds of thousands of years. A couple of months ago I was at a feminist debate in Bruxelles, where I discussed this topic with the Belgian philosopher Grietje Vandermassen, who, like me, wrote a book on evolutionary psychology and gender differences. She was adamant that women more often make the decision to stay home and raise the children because they in prehistoric times they were the ones taking care of the babies. This was their own choice, she claimed, based on an innate, long-evolved longing to raise your offspring, not a choice cultural stereotypes have taught us to make. Mothers made it because, unlike dads, taking care of babies is in their blood.

However, for this to be true, I countered, there must be solid evidence that modern dads are less capable of changing nappies and feeding babies mashed carrots and stroking the hair of little boys and girls who have the flu. And this, they are not. For instance: a study done by Barbara Risman of the University of North Carolina, interviewing 141 single fathers on their parenting behaviour shows how they effortlessly do everything that would traditionally be considered ‘mothering’.

The accounts are really quite touching, like the dad who lost his wife and told Risman: “They hurt themselves and need someone to rock them. They wake up from a bad dream in the middle of the night and need to be comforted. You don’t go out at night to pick up a woman. You’re a father.”

Another father in the same situation remembers: “I had to learn how to braid my daughters hair. Sandy had long hair and I realized you had to take care of it, because else it would look like nobody loved her. And it couldn’t just be any kind of braid, it had to be a special French braid.”

Are these fathers somehow defying their own nature? That seems even more unlikely when you look at fatherhood in different cultures. Of course there are cultures in which men hardly ever as much as have a look at their children, but there are also cultures in which the dads are particularly nurturing. The Aka for instance are a hunter-gatherer people from the Central African Republic, where the dads hold their babies or keep their children within arms reach more than half of the time. Some groups of Latin American natives share parenting duties equally between mother and father. At the Agta, hunter-gatherers from the Philippines, the women used to go out in groups to hunt small animals with bow and arrow, while the men would take care of the older children. (Infants who were still nursing would join the hunting trip bound to their mother’s backs.)

All this tells us a couple of important lessons. 1. There is a great deal of intercultural variation in behaviour we think is typically male or female, like taking care of children. 2. A lot of behaviour people in western societies consider to be innate or natural for women or men is in fact cultural. 3. This makes stereotypes even more important to our choices and behaviour then we thought.

=

So what do stereotypes mean for girls and women, when it comes to achievement in school and academics? For girls it sometimes means that they handicap themselves when it comes to stereotypically male things like doing math. To be clear: by the time they start high school, girls are a little better in mathematics than boys. And yet in the Netherlands, only about one in five girls who score over an average grade of 7.5 out of 10 choose to take math, physics and chemistry in the subsequent year. In boys, it’s three in five.

A French experiment shows that this has everything to do with stereotypes. Psychologists Pascal Huguet and Isabelle Régner went to 8 public schools, and separated all the children into two groups. The first was told that they were taking a test that would measure how good they were at drawing. The second group was told they were taking a math test. Next, both groups were given the same challenging geometrical, which they were to re-create.

For the boys it didn’t matter in which group they were placed. On average they all performed the same. But for the girls, it was another matter. The girls who were led to believe this was a drawing-test, markedly outperformed the girls who thought they were taking a math-test. The stereotype that art is for girls but math is for boys got the better of them.

But it isn’t just self-handicapping that keeps girls away from science. Stereotyping also leads to plain prejudice and discrimination. Research shows that high school math teachers, for instance, have a very different opinion about girls than about boys. If both have an average grade of 7 out of 10, they are very likely to advice the boy to take advanced math in the next year. They assume a boy with a grade of 7 shows great potential, has at least some talent en if he is willing to put in the effort he will easily pass the final exams.

A girl who scores an average of 7, on the other hand, is more likely to get the advice to drop math altogether. Teachers often regard this girl as having no real talent. They think she has earned her grade by being studious and working hard – a strategy that, unlike being talented, is assumed to have it’s limitations, so the teacher fears she will not be able to pass the finals. All of this assuming is usually done without a single conscious thought. Instead a teacher has a ‘gut feeling’ about a girl or a boy. That this gut feeling is really a stereotype disadvantaging girls and limiting their options escapes all notice.

=

For women in the academic world, the same basic mechanisms apply. On the one hand there is stereotypically induced self-handicapping, like not putting your hand up when you have something to say because you were raised in a culture where women are valued for being modest and where verbal assertiveness is associated with manliness.

And on the other hand you have plain prejudice, putting women at a disadvantage for reasons having nothing to do with academic performance whatsoever. Some people – mostly men – will claim this kind of, well, sexism doesn’t exist anymore, and that women who complain about it or demand policy changes are hairy legged feminists who just need something to nag about. These people are wrong. Sexism is very real at universities today.

It starts with the idea of the perfect employee. This perfect employee can work full-time without complaining. The perfect employee has no noticeable family life and no care-taking duties, so does not have to rush off in the middle of the day to pick up a sick kid from daycare. The perfect employee does not take four months of pregnancy leave at inconvenient times – which is always. The perfect employee is, by and large, male.

This image of the perfect employee has a lot of influence. Recently a girlfriend of mine was applying for a job as a post-doc, at Dutch university (not this one). During the interview, everything seemed to be going great. She had done most of her PHD-research at a prestigious university in the United States, had published in high impact journals and had worked with a very highly regarded professor who had written a glowing letter of recommendation. And then came the dreaded – and, mind you, illegal – question: “You’re 30 years old. You’re probably planning on having children soon, aren’t you?” She turned in her chair, not quite wanting to lie but not quite wanting to tell that she and her fiancé had decided to stop using birth control two months ago. She decided to tell the truth. Two days later, she heard another woman, with a weaker resumé, got the job. When asked, she told my girlfriend she flat-out lied about wanting children.

As always in these cases, sexism cannot be proven. My friend could have been rejected for any number of reasons. But science clearly proves that sexism exists. A classic experiment by two Swedish biologists, Christine Wennerås and Agnes Wold, shows as much. They decided to investigate the workings of the Swedish Medical Research Council, an institute responsible for giving out post-doc fellowships to eager biomedical scientist, who have to submit their cv’s, a list of publication and a research proposal. All this is then reviewed by one of 11 committees, who judge all applicants on three criteria: scientific competence, proposed methodology and the relevance of their research proposal.

In 1995, the year Wennerås and Wold conducted their research, 62 men and 52 women, with a mean age of 36 years, applied. So far, so good. But then something curious happened. The women, on average, were given less credit on all three of the committee’s criteria. This alone is strange, because there is no good reason to believe that women are less competent than men. What’s even stranger is just exactly how little the committees thought of the female applicants. When Wennerås and Wold made a list of all applicants, judging them by what is widely regarded an unbiased measure of academic performance, namely the number of published papers, the men didn’t outperform the women at all. But in the eyes of the committee, the best women on Wennerås and Wolds list were judged to be right at the same level as the worst men. No wonder most of the fellowships were awarded to men.

In the years following the publication of Wennerås and Wolds paper, this same mechanism has been proven in various different settings. Members of the American Psychological Association were sent the curriculum vitae of a job applicant, half of the time given a female name, the other half a male one. The cv’s with the male names were consistently appreciated with a higher starting salary, a greater likelihood to be offered tenure and a higher regard for their teaching skills. Another study showed that the same goes for male and female applicants for a job as head of a laboratory. Even letters of recommendation for female scientists are not as highly regarded, because their letters usually praise women’s communal behaviour, and these skills are considered less valuable than the agentic behaviour their male colleagues are usually recommended for.

And this is assuming women even get the chance to apply for a job. Most of vacancies for the higher positions on Dutch universities are filled using a closed procedure, in which formal and informal networks determine who get’s invited to apply. These networks are traditionally the domain of white males, putting both ethnic minorities and women at a significant disadvantage.

The problem with al these mechanisms holding women back is that they are at the same time very real and almost totally invisible. It is almost impossible for a female scientist to say: ‘I didn’t get this job for lack of a Y-chromosome’, or ‘I got passed for a position and sexism was involved.’ Not only because it is very hard to prove, but also because if you try to make such a case, there is a good chance that you are dismissed and ridiculed, like economist Edith Kuiper of the University of Amsterdam. She applied for a job as assistant professor, along with 6 other women and 18 men (which is, already, a bit crooked) and found herself in a situation where the committee changed the job description four times so the best suited candidate wouldn’t be her but a man. She sued the university, and was dragged through the mud by pundits and politicians for being a feminist crybaby who was trying to hide her own incompetence by making wild accusations of sexism.

So what do all these sexism and stereotypes accomplish?

Well, this is what gender equality looked like at Dutch universities in 2011. A leaky pipeline, loosing women at every step up the career ladder.

The next question is: what can be done? First of, it seems absolutely clear that policy changes must be made to fight sneaky sexism at every level. Most reports I’ve read recommended that at the very least these 3 measures have to be taken: 1. Either open procedures for all vacant positions – to work around the old boys network – or active recruitment of female scientists outside the beaten tracks. 2. Universities need to become more family-friendly, for the benefit of both their female and male employees. Taking pregnancy leave of working part time should not be punished by, for instance, having to meet the same publication criteria as your colleagues who worked full time all year around. And 3. Women should be given ample opportunity to make themselves more visible within the organization.

I would like to add a fourth: everybody should be made aware of the sneaky ways in which stereotypes shape our judgements and decisions, so that at an individual level we can all make an effort to combat our own gut feelings and be more rational and objective. This goes for women as well as men, since there is no evidence that females are less prone to all that subtle sexism I discussed.

=

So, finally, what can women do for themselves? How do you navigate sexist waters and conquer stereotypes and help your own career along? The advice I hear most often is this: let everybody know what your ambitions are. To many women this feels like inappropriate bragging, but you’ll be amazed how easy it is to just tell people what your dreams are for your own future. At the moment I am a columnist for one of the best newspapers in the country because I told one of their editors-in-chief repeatedly that I always dreamed about writing columns for them. I’m a regular contributor to several national radio shows because I spread the word that I loved doing more radio in the future. This stuff works.

The next best advice I take from Sheryl Sandberg, COO at Facebook. She recommends every woman to ignore her own feelings and instead ask herself: what would you do if you weren’t afraid? This is great advice, because the stereotypes women in our culture are brought up with teach us to be too careful, too sweet, too social and too modest. Most women would turn a job down if they don’t feel completely ready for it, Sandberg says. Don’t. Just bluff that you can do it, and than fake it until you make it. If you don’t feel sure enough of yourself to take a seat in the front row or put your hand up or demand an explanation or take a risk or ask if you can participate in this great research project, do it anyway. Is someone asks you why you did it, tell them why your great.

The point is this: if you feel like just a tiny little bit of an overconfident bitch, you’re probably right on track.

Photo credits: Let Toys be Toys (‘pinkwashing’), SocImages (‘How to be clever’ vs ‘How to be georgous’, baby shoes), Laura Menenti (‘Hurray, a sweet princess’ vs ‘A [soccer] star is born’)

Deze keynote lezing sprak ik 19 september 2013 uit op de Halkes Conferentie aan de Radboud Universiteit.

© Asha ten Broeke. Alle rechten voorbehouden.